Middle Ages

The Middle Ages (adjectival form: medieval) is a period of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The period followed the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, and preceded the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period in a three-period division of history: Classical, Medieval, and Modern. The term "Middle Ages" (medium aevum) was coined in the 15th century and reflects the view that this period was a deviation from the path of classical learning, a path supposedly reconnected by Renaissance scholarship.

The Early Middle Ages saw the continuation of trends set in Late Antiquity, depopulation, deurbanization, and increased barbarian invasion. North Africa and the Middle East, once part of the Eastern Roman Empire, were conquered by Islam. Later in the period, the establishment of the feudal system allowed a return to systemic agriculture. There was sustained urbanization in northern and western Europe. During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000 - 1300), Christian-oriented art and architecture flourished and Crusades were mounted to recapture the Holy Land. The influence of the emerging nation-state was tempered by the ideal of an international Christendom. The codes of chivalry and courtly love set rules for proper behavior, while the Scholastic philosophers attempted to reconcile faith and reason. Outstanding achievement in this period includes the Code of Justinian, the mathematics of Fibonacci and Oresme, the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, the painting of Giotto, and the poetry of Dante and Chaucer.

Contents |

Etymology and periodization

The Middle Ages is one of the three major periods in the most enduring scheme for analyzing European history: classical civilization (or Antiquity), the Middle Ages, and the modern period.[1] It is "Middle" in the sense of being between the two other periods in time. Humanist historians argued that Renaissance scholarship restored direct links to the classical period, thus bypassing the Medieval period. The term first appears in Latin in 1469 as media tempestas (middle time).[2] The term medium aevum (Middle Ages) is first recorded in 1604.[2]

Development of concept

Medieval historians did not, of course, think of themselves as being in the middle of history. Instead, they wrote history from a universal and theological perspective. They divided history into periods such as the "Six Ages" or the "Four Empires", with the present period being the last before the end of the world. They considered the Roman period, especially the time of the Apostles, a historical peak, followed by a long slide toward the Apocalypse.[3]

In the 1330s, humanist and poet Petrarch referred to pre-Christian times as antiqua (ancient) and to the Christian period as nova (new).[3] While retaining the theme of decline from the apogee of ancient Rome, Petrarch's division was not based on theology, but on a perception of cultural and political decline, especially the idea that Medieval Latin was inferior to Classical Latin. From Petrarch's Italian perspective, this new period (which included his own time) was an age of national eclipse. Leonardo Bruni was the first historian to use tripartite periodization in his History of the Florentine People (1442).[4] Bruni's first two periods were based on those of Petrarch, but he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire (1439–1453). Tripartite periodization became standard after German historian Christoph Cellarius published Universal History Divided into an Ancient, Medieval, and New Period (1683).

Start and end dates

The most commonly given start date for the Middle Ages is 476,[5] a date first given by Bruni.[4] This was when Romulus Augustus, the last Roman emperor in the West, abdicated. The western empire had already lost its military power by this time and Romulus Augustus was only a puppet emperor, so many historians object that this convention ascribes undue significance to an arbitrary year. In contrast, Biondo used the sack of Rome in 410 by the Goths as the beginning of the period.[3] In the history of Scandinavia, the Middle Ages followed prehistory during the 11th century, when the rulers converted to Christianity and substantial written records began to appear. A similar shift from prehistory to the Middle Ages occurred in Estonia and Latvia during the 13th century.

For Europe as a whole, the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 is commonly used as the end date of the Middle Ages. Depending on the context, other events, such as the invention of the moveable type printing press in Europe by Johann Gutenberg (1455), the fall of Muslim Spain or Christopher Columbus's voyage to America (both 1492), can be used. For Italy, 1401, the year the contract was awarded to build the north doors of the Florence Baptistery, is often used. In contrast, English historians often use the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485) to mark the end of the period.[6] For Spain, the death of King Ferdinand II (1516) is used.[7]

Subdivisions

Historians in the Romance languages tend to divide the Middle Ages into two parts: an earlier "High" and later "Low" period. English-speaking historians, following their German counterparts, generally subdivide the Middle Ages into three intervals: "Early", "High" and "Late".[1] Belgian historian Henri Pirenne and Dutch historian Johan Huizinga popularized the following subdivisions in the early 20th century: the Early Middle Ages (476-1000), the High Middle Ages (1000–1300), and the Late Middle Ages (1300–1453).

The later Roman Empire

The Roman empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century. The following two centuries witnessed the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories. The Emperor Diocletian split the empire into separately administered eastern and western halves in 285. The division between east and west was encouraged by Constantine, who refounded the city of Byzantium as the new capital, Constantinople, in 330.

Military expenses increased steadily during the 4th century, even as Rome's neighbours became restless and increasingly powerful. Tribes who previously had contact with the Romans as trading partners, rivals, or mercenaries had sought entrance to the empire and access to its wealth throughout the 4th century.

Diocletian's reforms had created a strong governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army.[8] These reforms bought the Empire time, but they demanded money. Roman power had been maintained by its well-trained and equipped armies. These armies, however, were a constant drain on the Empire's finances. As warfare became more dependent on heavy cavalry, the infantry-based Roman military started to lose its advantage against its rivals. The defeat in 378 at the Battle of Adrianople, at the hands of mounted Gothic lancers, destroyed much of the Roman army and left the western empire undefended.[8] Without a strong army, the empire was forced to accommodate the large numbers of Germanic tribes who sought refuge within its frontiers.

Known in traditional historiography collectively as the "barbarian invasions", the Migration Period, or the Völkerwanderung ("wandering of the peoples"), this migration was a complicated and gradual process. Some of these "barbarian" tribes rejected the classical culture of Rome, while others admired and aspired to it. In return for land to farm and, in some regions, the right to collect tax revenues for the state, federated tribes provided military support to the empire. Other incursions were small-scale military invasions of tribal groups assembled to gather plunder. The Huns, Bulgars, Avars, and Magyars all raided the Empire's territories and terrorised its inhabitants. Later, Slavic and Germanic peoples would settle the lands previously taken by these tribes. The most famous invasion culminated in the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410, the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to an enemy.

By the end of the 5th century, Roman institutions were crumbling. Some early historians have given this period of societal collapse the epithet of "Dark Ages" because of the contrast to earlier times. The last emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the barbarian king Odoacer in 476.[8] The Eastern Roman Empire (conventionally referred to as the "Byzantine Empire" after the fall of its western counterpart) had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. Even though Byzantine emperors maintained a claim over the territory, and no "barbarian" king dared to elevate himself to the position of Emperor of the west, Byzantine control of most of the West could not be sustained; the renovatio imperii ("imperial restoration", entailing reconquest of the Italian peninsula and Mediterranean periphery) by Justinian was the sole, and temporary, exception.

As Roman authority disappeared in the west, cities, literacy, trading networks and urban infrastructure declined. Where civic functions and infrastructure were maintained, it was mainly by the Christian Church. Augustine of Hippo is an example of one bishop who became a capable civic administrator.

Early Middle Ages

Breakdown of Roman society

The breakdown of Roman society was dramatic. The patchwork of petty rulers was incapable of supporting the depth of civic infrastructure required to maintain libraries, public baths, arenas, and major educational institutions. Any new building was on a far smaller scale than before. The social effects of the fracture of the Roman state were manifold. Cities and merchants lost the economic benefits of safe conditions for trade and manufacture, and intellectual development suffered from the loss of a unified cultural and educational milieu of far-ranging connections.

As it became unsafe to travel or carry goods over any distance, there was a collapse in trade and manufacture for export. The major industries that depended on long-distance trade, such as large-scale pottery manufacture, vanished almost overnight in places like Britain. Whereas sites like Tintagel in Cornwall (the extreme southwest of modern day England) had managed to obtain supplies of Mediterranean luxury goods well into the 6th century, this connection was now lost.

Between the 5th and 8th centuries, new peoples and powerful individuals filled the political void left by Roman centralized government. Germanic tribes established regional hegemonies within the former boundaries of the Empire, creating divided, decentralized kingdoms like those of the Ostrogoths in Italy, the Suevi in Gallaecia, the Visigoths in Hispania, the Franks and Burgundians in Gaul and western Germany, the Angles and the Saxons in Britain, and the Vandals in North Africa.

Roman landholders beyond the confines of city walls were also vulnerable to extreme changes, and they could not simply pack up their land and move elsewhere. Some were dispossessed and fled to Byzantine regions; others quickly pledged their allegiances to their new rulers. In areas like Spain and Italy, this often meant little more than acknowledging a new overlord, while Roman forms of law and religion could be maintained. In other areas, where there was a greater weight of population movement, it might be necessary to adopt new modes of dress, language, and custom.

The Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries of the Persian Empire, Roman Syria, Roman Egypt, Roman North Africa, Visigothic Spain, Sicily and southern Italy eroded the area of the Roman Empire and controlled strategic areas of the Mediterranean. By the end of the 8th century, the former Western Roman Empire was decentralized and overwhelmingly rural.

Church and monasticism

The Catholic Church was the major unifying cultural influence, preserving its selection from Latin learning, maintaining the art of writing, and a centralized administration through its network of bishops. Some regions that were populated by Catholics were conquered by Arian rulers, which provoked much tension between Arian kings and the Catholic hierarchy. Clovis I of the Franks is a well-known example of a barbarian king who chose Catholic orthodoxy over Arianism. His conversion marked a turning point for the Frankish tribes of Gaul.

Bishops were central to Middle Age society due to the literacy they possessed. As a result, they often played a significant role in governance. However, beyond the core areas of Western Europe, there remained many peoples with little or no contact with Christianity or with classical Roman culture. Martial societies such as the Avars and the Vikings were still capable of causing major disruption to the newly emerging societies of Western Europe.

The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of monasticism within the west. Although the impulse to withdraw from society to focus upon a spiritual life is experienced by people of all cultures, the shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated in the deserts of Egypt and Syria.[9] The style of monasticism that focuses on community experience of the spiritual life, called cenobitism, was pioneered by the saint Pachomius in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through hagiographical literature such as the Life of Saint Anthony.[9]

Saint Benedict wrote the definitive Rule for western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an abbot.[9] The style of monasticism based upon the Benedictine Rule spread widely rapidly across Europe, replacing small clusters of cenobites. Monks and monasteries had a deep effect upon the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, bases for mission, and proselytization. They were the main outposts of education and literacy.

Carolingians

A nucleus of power developed in a region of northern Gaul and developed into kingdoms called Austrasia and Neustria. These kingdoms were ruled for three centuries by a dynasty of kings called the Merovingians, after their mythical founder Merovech. The history of the Merovingian kingdoms is one of family politics that frequently erupted into civil warfare between the branches of the family. The legitimacy of the Merovingian throne was granted by a reverence for the bloodline, and, even after powerful members of the Austrasian court, the mayors of the palace, took de facto power during the 7th century, the Merovingians were kept as ceremonial figureheads. The Merovingians engaged in trade with northern Europe through Baltic trade routes known to historians as the Northern Arc trade, and they are known to have minted small-denomination silver pennies called sceattae for circulation. Aspects of Merovingian culture could be described as "Romanized", such as the high value placed on Roman coinage as a symbol of rulership and the patronage of monasteries and bishoprics. Some have hypothesized that the Merovingians were in contact with Byzantium.[10] However, the Merovingians also buried the dead of their elite families in grave mounds and traced their lineage to a mythical sea beast called the Quinotaur.[10]

The 7th century was a tumultuous period of civil wars between Austrasia and Neustria. Such warfare was exploited by the patriarch of a family line, Pippin of Herstal, who curried favour with the Merovingians and had himself installed in the office of Mayor of the Palace at the service of the King. From this position of great influence, Pippin accrued wealth and supporters. Later members of his family line inherited the office, acting as advisors and regents. The dynasty took a new direction in 732, when Charles Martel won the Battle of Tours, halting the advance of Muslim armies across the Pyrenees.

The Carolingian dynasty, as the successors to Charles Martel are known, officially took the reins of the kingdoms of Austrasia and Neustria in a coup of 753 led by Pippin III. A contemporary chronicle claims that Pippin sought, and gained, authority for this coup from the Pope.[11] Pippin's successful coup was reinforced with propaganda that portrayed the Merovingians as inept or cruel rulers and exalted the accomplishments of Charles Martel and circulated stories of the family's great piety. At the time of his death in 783, Pippin left his kingdoms in the hands of his two sons, Charles and Carloman. When Carloman died of natural causes, Charles blocked the succession of Carloman's minor son and installed himself as the king of the united Austrasia and Neustria. This Charles, known to his contemporaries as Charles the Great or Charlemagne, embarked in 774 upon a program of systematic expansion that would unify a large portion of Europe. In the wars that lasted just beyond 800, he rewarded loyal allies with war booty and command over parcels of land. Much of the nobility of the High Middle Ages was to claim its roots in the Carolingian nobility that was generated during this period of expansion.[11]

The Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas Day of 800 is frequently regarded as a turning-point in medieval history, because it filled a power vacancy that had existed since 476. It also marks a change in Charlemagne's leadership, which assumed a more imperial character and tackled difficult aspects of controlling a medieval empire. He established a system of diplomats who possessed imperial authority, the missi, who in theory provided access to imperial justice in the farthest corners of the empire.[12] He also sought to reform the Church in his domains, pushing for uniformity in liturgy and material culture.

Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne's court in Aachen was the centre of a cultural revival that is sometimes referred to as the "Carolingian Renaissance". This period witnessed an increase of literacy, developments in the arts, architecture, and jurisprudence, as well as liturgical and scriptural studies. The English monk Alcuin was invited to Aachen, and brought with him the precise classical Latin education that was available in the monasteries of Northumbria. The return of this Latin proficiency to the kingdom of the Franks is regarded as an important step in the development of medieval Latin. Charlemagne's chancery made use of a type of script currently known as Carolingian minuscule, providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. After the decline of the Carolingian dynasty, the rise of the Saxon Dynasty in Germany was accompanied by the Ottonian Renaissance.

See also the careers of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Breakup of the Carolingian empire

While Charlemagne continued the Frankish tradition of dividing the regnum (kingdom) between all his heirs (at least those of age), the assumption of the imperium (imperial title) supplied a unifying force not available previously. Charlemagne was succeeded by his only legitimate son of adult age at his death, Louis the Pious.

Louis's long reign of 26 years was marked by numerous divisions of the empire among his sons and, after 829, numerous civil wars between various alliances of father and sons against other sons to determine a just division by battle. The final division was made at Crémieux in 838. The Emperor Louis recognized his eldest son Lothair I as emperor and confirmed him in the Regnum Italicum (Italy). He divided the rest of the empire between Lothair and Charles the Bald, his youngest son, giving Lothair the opportunity to choose his half. He chose East Francia, which comprised the empire on both banks of the Rhine and eastwards, leaving Charles West Francia, which comprised the empire to the west of the Rhineland and the Alps. Louis the German, the middle child, who had been rebellious to the last, was allowed to keep his subregnum of Bavaria under the suzerainty of his elder brother. The division was not undisputed. Pepin II of Aquitaine, the emperor's grandson, rebelled in a contest for Aquitaine, while Louis the German tried to annex all of East Francia. In two final campaigns, the emperor defeated both his rebellious descendants and vindicated the division of Crémieux before dying in 840.

A three-year civil war followed his death. At the end of the conflict, Louis the German was in control of East Francia and Lothair was confined to Italy. By the Treaty of Verdun (843), a kingdom of Middle Francia was created for Lothair in the Low Countries and Burgundy, and his imperial title was recognized. East Francia would eventually morph into the Kingdom of Germany and West Francia into the Kingdom of France, around both of which the history of Western Europe can largely be described as a contest for control of the middle kingdom. Charlemagne's grandsons and great-grandsons divided their kingdoms between their sons until all the various regna and the imperial title fell into the hands of Charles the Fat by 884. He was deposed in 887 and died in 888, to be replaced in all his kingdoms but two (Lotharingia and East Francia) by non-Carolingian "petty kings". The Carolingian Empire was destroyed, though the imperial tradition would eventually lead to the Holy Roman Empire in 962.

The breakup of the Carolingian Empire was accompanied by the invasions, migrations, and raids of external foes as not seen since the Migration Period. The Atlantic and northern shores were harassed by the Vikings, who forced Charles the Bald to issue the Edict of Pistres against them and who besieged Paris in 885–886. The eastern frontiers, especially Germany and Italy, were under constant Magyar assault until their great defeat at the Battle of the Lechfeld in 955.[13] The Saracens also managed to establish bases at Garigliano and Fraxinetum, to sack Rome in 846 and to conquer the islands of Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily, and their pirates raided the Mediterranean coasts, as did the Vikings. The Christianization of the pagan Vikings provided an end to that threat.

Art and architecture

Few large stone buildings were attempted between the Constantinian basilicas of the 4th century, and the 8th century. At this time, the establishment of churches and monasteries, and a comparative political stability, caused the development of a form of stone architecture loosely based upon Roman forms and hence later named Romanesque. Where available, Roman brick and stone buildings were recycled for their materials. From the fairly tentative beginnings known as the First Romanesque, the style flourished and spread across Europe in a remarkably homogeneous form. The features are massive stone walls, openings topped by semi-circular arches, small windows, and, particularly in France, arched stone vaults and arrows.

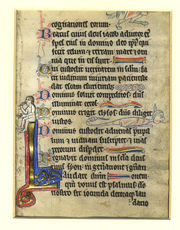

In the decorative arts, Celtic and Germanic barbarian forms were absorbed into Christian art, although the central impulse remained Roman and Byzantine. High quality jewellery and religious imagery were produced throughout Western Europe; Charlemagne and other monarchs provided patronage for religious artworks such as reliquaries and books. Some of the principal artworks of the age were the fabulous Illuminated manuscripts produced by monks on vellum, using gold, silver, and precious pigments to illustrate biblical narratives. Early examples include the Book of Kells and many Carolingian and Ottonian Frankish manuscripts.

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages were characterized by the urbanization of Europe, military expansion, and intellectual revival that historians identify between the 11th century and the end of the 13th century. This revival was aided by the conversion of the raiding Scandinavians and Hungarians to Christianity, as well as the assertion of power by castellans to fill the power vacuum left by the Carolingian decline. The High Middle Ages saw an explosion in population. This population flowed into towns, sought conquests abroad, or cleared land for cultivation. The cities of antiquity had been clustered around the Mediterranean. By 1200, the growing urban centres were in the centre of the continent, connected by roads or rivers. By the end of this period, Paris might have had as many as 200,000 inhabitants.[14] In central and northern Italy and in Flanders, the rise of towns that were self-governing to some degree within their territories stimulated the economy and created an environment for new types of religious and trade associations. Trading cities on the shores of the Baltic entered into agreements known as the Hanseatic League, and Italian city-states such as Venice, Genoa, and Pisa expanded their trade throughout the Mediterranean. This period marks a formative one in the history of the western state as we know it, for kings in France, England, and Spain consolidated their power during this period, setting up lasting institutions to help them govern. Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their sedentarization and conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers. Hungary, especially, became the "Gate to Europe" from Asia, and bastion of Christianity against the invaders from the East for the next 600 years.[15] The Papacy, which had long since created an ideology of independence from the secular kings, first asserted its claims to temporal authority over the entire Christian world. The entity that historians call the Papal Monarchy reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of Innocent III. Northern Crusades and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously pagan regions in the Baltic and Finnic northeast brought the forced assimilation of numerous native peoples to the European entity. With the brief exception of the Kipchak and Mongol invasions, major barbarian incursions ceased.[16]

Crusades

The Crusades were armed pilgrimages intended to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim control. Jerusalem was part of the Muslim possessions won during a rapid military expansion in the 7th century through the Near East, Northern Africa, and Anatolia (in modern Turkey). The first Crusade was preached by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095 in response to a request from the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos for aid against further advancement. Urban promised indulgence to any Christian who took the Crusader vow and set off for Jerusalem. The resulting fervour that swept through Europe mobilized tens of thousands of people from all levels of society, and resulted in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, as well as other regions. The movement found its primary support in the Franks; it is by no coincidence that the Arabs referred to Crusaders generically as "Franj".[17] Although they were minorities within this region, the Crusaders tried to consolidate their conquests as a number of Crusader states – the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as well as the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli (collectively Outremer). During the 12th century and 13th century, there were a series of conflicts between these states and surrounding Islamic ones. Crusades were essentially resupply missions for these embattled kingdoms. Military orders such as the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller were formed to play an integral role in this support.

By the end of the Middle Ages, the Christian Crusaders had captured all the Islamic territories in modern Spain, Portugal, and Southern Italy. Meanwhile, Islamic counter-attacks had retaken all the Crusader possessions on the Asian mainland, leaving a de facto boundary between Islam and western Christianity that continued until modern times.

Substantial areas of northern Europe also remained outside Christian influence until the 11th century or later; these areas also became crusading venues during the expansionist High Middle Ages. Throughout this period, the Byzantine Empire was in decline, having peaked in influence during the High Middle Ages. Beginning with the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the empire underwent a cycle of decline and renewal, including the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. After that, Andrew II of Hungary assembled the biggest army in the history of the Crusades, and moved his troops as a leading figure in the Fifth Crusade, reaching Cyprus and later Lebanon, coming back home in 1218.[18]

Despite another short upswing following the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the empire continued to deteriorate.

Science and technology

During the early Middle Ages and the Islamic Golden Age, Islamic philosophy, science, and technology were more advanced than in Western Europe. Islamic scholars both preserved and built upon earlier Ancient Greek and Roman traditions and added their own inventions and innovations. Islamic al-Andalus passed much of this on to Europe (see Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe). The replacement of Roman numerals with the decimal positional number system and the invention of algebra allowed more advanced mathematics. Another consequence was that the Latin-speaking world regained access to lost classical literature and philosophy. Latin translations of the 12th century fed a passion for Aristotelian philosophy and Islamic science that is frequently referred to as the Renaissance of the 12th century. Meanwhile, trade grew throughout Europe as the dangers of travel were reduced, and steady economic growth resumed. Cathedral schools and monasteries ceased to be the sole sources of education in the 11th century when universities were established in major European cities. Literacy became available to a wider class of people, and there were major advances in art, sculpture, music, and architecture. Large cathedrals were built across Europe, first in the Romanesque, and later in the more decorative Gothic style.

During the 12th and 13th century in Europe, there was a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. The period saw major technological advances, including the invention of cannon, spectacles, and artesian wells, and the cross-cultural introduction of gunpowder, silk, the compass, and the astrolabe from the east. There were also great improvements to ships and the clock. The latter advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Exploration. At the same time, huge numbers of Greek and Arabic works on medicine and the sciences were translated and distributed throughout Europe. Aristotle especially became very important, his rational and logical approach to knowledge influencing the scholars at the newly forming universities which were absorbing and disseminating the new knowledge during the 12th Century Renaissance.

Changes

Monastic reform became an important issue during the 11th century, when elites began to worry that monks were not adhering to their Rules with the discipline that was required for a good religious life. During this time, it was believed that monks were performing a very practical task by sending their prayers to God and inducing Him to make the world a better place for the virtuous. The time invested in this activity would be wasted, however, if the monks were not virtuous. The monastery of Cluny, founded in the Mâcon in 909, was founded as part of a larger movement of monastic reform in response to this fear.[19] It was a reformed monastery that quickly established a reputation for austerity and rigour. Cluny sought to maintain the high quality of spiritual life by electing its own abbot from within the cloister, and maintained an economic and political independence from local lords by placing itself under the protection of the Pope.[14] Cluny provided a popular solution to the problem of bad monastic codes, and in the 11th century its abbots were frequently called to participate in imperial politics as well as reform monasteries in France and Italy.

Monastic reform inspired change in the secular church, as well. The ideals that it was based upon were brought to the papacy by Pope Leo IX on his election in 1049, providing the ideology of clerical independence that fuelled the Investiture Controversy in the late 11th century. The Investiture Controversy involved Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who initially clashed over a specific bishop's appointment and turned into a battle over the ideas of investiture, clerical marriage, and simony. The Emperor, as a Christian ruler, saw the protection of the Church as one of his great rights and responsibilities. The Papacy, however, had begun insisting on its independence from secular lords. The open warfare ended with Henry IV's occupation of Rome in 1085 and the death of the Pope several months later, but the issues themselves remained unresolved even after the compromise of 1122 known as the Concordat of Worms. The conflict represents a significant stage in the creation of a papal monarchy separate from lay authorities. It also had the permanent consequence of empowering German princes at the expense of the German emperors.[14]

The High Middle Ages was a period of great religious movements. The Crusades, which have already been mentioned, have an undeniable religious aspect. Monastic reform was similarly a religious movement effected by monks and elites. Other groups sought to participate in new forms of religious life. Landed elites financed the construction of new parish churches in the European countryside, which increased the Church's impact upon the daily lives of peasants. Cathedral canons adopted monastic rules, groups of peasants and laypeople abandoned their possessions to live like the Apostles, and people formulated ideas about their religion that were deemed heretical. Although the success of the 12th century papacy in fashioning a Church that progressively affected the daily lives of everyday people cannot be denied, there are still indicators that the tail could wag the dog. The new religious groups called the Waldensians and the Humiliati were condemned for their refusal to accept a life of cloistered monasticism. In many aspects, however, they were not very different from the Franciscans and the Dominicans, who were approved by the papacy in the early 13th century (the Franciscan and the Dominican friars developed the popular sermon). The picture that modern historians of the religious life present is one of great religious zeal welling up from the peasantry during the High Middle Ages, with clerical elites striving, only sometimes successfully, to understand and channel this power into familiar paths.

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages were a period initiated by calamities and upheavals. During this time, agriculture was affected by a climate change that has been documented by climate historians, and was felt by contemporaries in the form of periodic famines, including the Great Famine of 1315-1317.[20] Medieval Britain was afflicted by 95 famines,[21] and France suffered the effects of 75 or more in the same period.[22] The Black Death, a disease that spread among the populace like wildfire, killed as much as a third of the population in the mid-14th century.[23] In some regions, the toll was higher than one half of the population. Towns were especially hard-hit because of the crowded conditions. Large areas of land were left sparsely inhabited, and in some places fields were left unworked. Because of the sudden decline in available labourers, the price of wages rose as landlords sought to entice workers to their fields. Workers also felt that they had a right to greater earnings, and popular uprisings broke out across Europe. Even the king Louis I of Hungary was forced to stop his long war against the Kingdom of Naples in 1347, because of the deaths in the Italian region. The Black Death soon took the life of Louis I's wife, Margaret, daughter of the German emperor Charles IV, and as well few Hungarians, although the negative consequences of this disease in the Kingdom of Hungary were relatively mild.

This period of stress, paradoxically, witnessed creative social, economic, and technological responses that laid the groundwork for further great changes in the Early Modern Period. It was also a period when the Catholic Church was increasingly divided against itself. During the time of the Western Schism, the Church was led by as many as three popes at one time. The divisiveness of the Church undermined papal authority, and allowed the formation of national churches.

State resurgence

The Late Middle Ages also witnessed the rise of strong, royalty-based nation-states, particularly the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of France, and the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (Aragon, Castile, Navarre, and Portugal).

The long conflicts of this time, such as the Hundred Years' War fought between England and France, strengthened royal control over the kingdoms, even though they were extremely hard on the peasantry. Kings profited from warfare by gaining land.

France shows clear signs of a growth in royal power during the 14th century, from the active persecution of heretics and lepers, expulsion of the Jews, and the dissolution of the Knights Templar. In all of these cases, undertaken by Philip IV, the king confiscated land and wealth from these minority groups.[14] The conflict between Philip and Pope Boniface VIII, a conflict which began over Philip's unauthorized taxation of clergy, ended with the violent death of Boniface and the installation of Pope Clement V, a weak, French-controlled pope, in Avignon. This action enhanced French prestige, at the expense of the papacy.

England, too, began the 14th century with warfare and expansion. Edward I waged war against the Principality of Wales and the Kingdom of Scotland, with mixed success, to assert what he considered his right to the entire island of Great Britain.

Both the Kings of France and the Kings of England of this period presided over effective states administered by literate bureaucrats, and sought baronial consent for their decisions through early versions of parliamentary systems, called the Estates General in France and the Parliament in England. Towns and merchants allied with kings during the 15th century, allowing the kings to distance themselves further from the territorial lords. As a result of the power gained during the 14th and 15th centuries, late medieval kings built truly sovereign states, which were able to impose taxes, declare war, and create and enforce laws, all by the will of the king.[24] Kings encouraged cohesion in their administration by appointing ministers with broad ambitions and a loyalty to the state.[24] By the last half of the 15th century, kings like Henry VII of England and Louis XI of France were able to rule without much baronial interference.

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a conflict between France and England lasting 116 years, from 1337 to 1453. It was fought primarily over claims by the English kings to the French throne and was punctuated by several brief and two lengthy periods of peace before it finally ended in the expulsion of the English from France, except for the Calais Pale. Thus, the war was a series of conflicts, and is commonly divided into three or four phases: the Edwardian War (1337–1360), the Caroline War (1369–1389), the Lancastrian War (1415–1429), and the slow decline of English fortunes after the appearance of Joan of Arc (1429–1453). Though primarily a dynastic conflict, the war gave impetus to ideas of both French and English nationality. Militarily, it saw the introduction of new weapons and tactics, which eroded the older system of feudal armies dominated by heavy cavalry. The first standing armies in Western Europe since the time of the Western Roman Empire were introduced for the war, thus changing the role of the peasantry. For all this, as well as for its long duration, it is often viewed as one of the most significant conflicts in the history of medieval warfare.

Controversy within the Church

The troubled 14th century saw both the Avignon Papacy of 1305–1378, also called the Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy (a reference to the Babylonian Captivity of the Jews), and the so-called Western Schism that lasted from 1378 to 1418. The practice of granting papal indulgences, fairly commonplace since the 11th century, was reformulated and explicitly monetized in the 14th century.[14] Indulgences became an important source of revenue for the Church, revenue that filtered through parish churches to bishops and then to the pope himself. This was viewed by many as a corruption of the Church. In the early years of the 15th century, after a century of turmoil, ecclesiastical officials convened in Constance in 1417 to discuss a resolution to the Schism.[14] Traditionally, councils needed to be called by the Pope, and none of the contenders were willing to call a council and risk being unseated. The act of convening a council without papal approval was justified by the argument that the Church was represented by the whole population of the faithful. The council deposed the warring popes and elected Martin V. The turmoil of the Church, and the perception that it was a corrupted institution, sapped the legitimacy of the papacy within Europe and fostered greater loyalty to regional or national churches. Martin Luther published objections to the Church. Although his disenchantment had long been forming, the denunciation of the Church was precipitated by the arrival of preachers raising money to rebuild the Basilica of Saint Peter in Rome. Luther might have been silenced by the Church, but the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I brought the imperial succession to the forefront of concern. Lutherans' split with the Church in 1517, and the subsequent division of Catholicism into Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anabaptism, put a definitive end to the unified Church built during the Middle Ages.

Europe in 1328 |

Europe in the 1430s |

Europe in the 1470s |

Religion

- Church and state in medieval Europe

- The Crusades

- Pilgrimage

- Papacy

- Medieval Inquisition

- Heresy (for example, Arian; Cathar; John Wyclif; Hussites)

- Monastic orders

- Benedictines

- Carthusians

- Cistercians

- Mendicant friars

- Franciscans

- Dominicans

- Carmelites

- Augustinians

- Judaism

- Islam (Western Europe): Al-Andalus; Emirate of Sicily

- Islam (Eastern Europe): Golden Horde; Crimean Khanate; Sultanate of Rûm & Ottoman Empire

- Reconquista

- Ottoman wars in Europe

The Middle Ages outside Europe

The periodization of the "Middle-Ages" can be dated in rough similarity to other cultures besides the European kingdoms of the era. The Middle Ages are a distinct period both in Islamic, Euroasian and Japanese kingdoms. In-fact, throughout the Middle Ages, the newly-founded religion of Islam had experienced an era of Imperial conquests and political and economical status unmatched by parallel European kingdoms, with the possible exception of Constantinopolis. Many similarities are shared by the parallel Islamic and Christian societies of the period.[25]

The Middle Ages in the Middle East

The inhabitants of the Christian, Arabic and Persian lands to be occupied by the Islam Emirate in the Middle Ages, did not consider themselves "Middle-Eastern" relative to a more westren-based center of political influence. Hence, the modern political name "Middle East" is irrelevant during Mediaeval periods, whereas the contemporary Arabic term is "Mashrik".

The Middle Ages in Byzantine Anatolia

The Middle Ages in the Euroasian Steppe

Gallery

The Franks Casket, an Anglo-Saxon box made of whale's bone, 8th century |

An illuminated initial from the Sacramentary of Drogon, c. 930 |

Medallion of Christ from an Icon Frame, ca. 1100 |

The typanum of Christ in Majesty at Autun Cathedral, 12th century |

.jpg) Lamentation, Giotto di Bondone, ca. 1305 |

Historians

- Geoffrey of Monmouth

- Geraldis Cambrensis

- Placido Puccinelli (1609–1685), - Italy

- Marc Bloch (1886–1944, French) France, methodology; Annales School

- John Boswell (1947–1994) - Homosexuality

- Norman Cantor (1930–2004), England, historiography

- Georges Duby (1924–1996), France; Annales School

- François-Louis Ganshof (1895–1980), Dutch

- Patrick Geary

- Johan Huizinga Dutch

- George Sarton, science

- Jacques Le Goff, French, Annales School

- Rev. F. X. Martin (Irish) - Mediævalist and campaigner

- Rosamond McKitterick - Frankish and Carolingian history

- Henri Pirenne (1862–1935) - the "Pirenne Thesis" downplays barbarian invasions and emphasizes role of Islam[26]

- Eileen Power

- Miri Rubin - religion

- Stephen Runciman (1903–2000) - the Crusades

- Richard Southern (1912–2001), religion

- Sidney Painter

- John Julius Norwich

- Régine Pernoud (1909–1998)

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Power, Daniel (2006).The central Middle Ages: Europe 950-1320. The short Oxford history of Europe (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 304 ISBN 9780199253128.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Albrow, Martin, The global age: state and society beyond modernity (1997), p. 205.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "History of the Idea of the Renaissance"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Leonardo Bruni, James Hankins, History of the Florentine people, Volume 1, Books 1-4, (2001), p. xvii.

- ↑ "Ages Middle Ages". Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004.

- ↑ Prudames, David. Lottery cash kicks off search for the real Bosworth battlefield, 24 Hour Museum 20 January 2005.

- ↑ Henry Kamen. Spain 1469-1714. 2005. ISBN 0-582-78464-6 - p. 29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society (first ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804726302.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Lawrence, C.H (2001). Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages (third ed.). Longman. ISBN 0582404274.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wood, Ian (1995). The Merovingian Kingdoms 450-751. Pearson Education. ISBN 0582493722.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812213424.

- ↑ Although the missus dominicus makes appearances during the second half of the 8th century, it is after 800 that they were institutionalized. Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812213424.

- ↑ The Magyars of Hungary.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Rosenwein, Barbara H (2001). A Short History of the Middle Ages. Broadview Press. ISBN 1551112906.

- ↑ History of Hungary

- ↑ The Destruction of Kiev.

- ↑ Maalouf, Amin (1989). Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Schocken. ISBN 0805208984.

- ↑ Andrew II of Hungary and the fifth Crusade

- ↑ Rosenwein, Barbara H (1982). Rhinoceros Bound: Cluny in the Tenth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0812278305.

- ↑ The Great Famine (1315-1317) and the Black Death (1346-1351). Lynn Harry Nelson. The University of Kansas.

- ↑ Poor studies will always be with us. By James Bartholomew. Telegraph. 2004-08-07.

- ↑ Famine. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Black Death (epidemic). Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Kagan, Donald; Ozment, Steven, Turner, Frank M. (1993). The Western Heritage: Since 1300 (eighth ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131828835.

- ↑ A lesson of Dr. Debora Thor regarding the History of Medival Islam, Bar-Ilan University

- ↑ Kenneth W. Frank, "Pirenne Again: A Muslim Viewpoint", The History Teacher, Vol. 26, No. 3 (May, 1993), pp. 371-383 in JSTOR

- Strayer, Joseph R. (1989). Joseph R. Strayer. ed. Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-684-19073-7.

External links

- Internet Medieval Sourcebook Project Primary source archive

- The Online Reference Book of Medieval Studies Academic peer reviewed articles

- The Labyrinth Resources for Medieval Studies.

- NetSERF The Internet Connection for Medieval Resources.

- The Middle Ages - an informational site for teachers and students

- Information from the Medieval Period.

- De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History

- Medievalists.net

- Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, featuring lavish illustrations and a wide range of scripts from Western Europe and the Middle East, Center for Digital Initiatives, University of Vermont Libraries

- Medievalmap.org Interactive maps of the Medieval era (Flash plug-in required)

- Middle Ages, library of books available at Internet Archive

- "MacKinney Collection of Medieval Medical Illustrations"

- Medieval Realms Learning resources from the British Library including studies of beautiful medieval manuscripts

- Medieval Knights Medieval Knights is a medieval educational resource site geared to students and medieval enthusiasts.

- Charles Raymond Beazley. A Note-Book of Mediaeval History, A.D. 323- A.D. 1453. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1917. Annotated time-line of medieval history.

- The Soldier in later Medieval England Detailed service records of 250,000 medieval soldiers are online.

- Clio History Journal, Medieval History Page

- The Medieval Review

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||